Akka with JRuby

This week I completed my work project and had a spare day to do some experimentation. I dabble sometimes with Scala which I think offers a cool combination of FP, OO and concurrency management. Akka is a middleware framework which works with Scala (and also Java) and provides an excellent abstraction to manage concurrency. Instead of dealing with threads, thread pools and low level synchronization we manage concurrency with something called as Actors.

From Akka’s site - “Actors are objects which encapsulate state and behavior, they communicate exclusively by exchanging messages which are placed into the recipient’s mailbox. In a sense, actors are the most stringent form of object-oriented programming, but it serves better to view them as persons: while modeling a solution with actors, envision a group of people and assign sub-tasks to them, arrange their functions into an organizational structure and think about how to escalate failure (all with the benefit of not actually dealing with people, which means that we need not concern ourselves with their emotional state or moral issues). The result can then serve as a mental scaffolding for building the software implementation”.

I think this is a great abstraction, dealing with people rather than threads :). To understand more about Akka see this presentation here.

In my last blog, I talked about the advantages of using threads and the performace boost they give. I also warned about proper concurrency management when introducing threads to an application. If you need concurrency on a JRuby platform, Akka should be able to help you. After all anything that works on JVM should work on JRuby as well.

With this in mind I wrote a simple “Hello World” in JRuby and Akka. To make this work, download the Akka distribution, create a folder and copy the following jars from the downloaded Akka ditribution in it -

- akka-actor-xx.jar

- config-xx.jar

- scala-library.jar

In the same folder create hello.rb like this -

require 'java'require 'scala-library.jar'require 'config-0.3.1.jar'require 'akka-actor-2.0.3.jar'

java_import 'java.io.Serializable'java_import 'akka.actor.UntypedActor'java_import 'akka.actor.ActorRef'java_import 'akka.actor.ActorSystem'java_import 'akka.actor.Props'

class Greeting include Serializable

attr_reader :who

def initialize(who) @who = who endend

class GreetingActor < UntypedActor class << self alias_method :apply, :new alias_method :create, :new end

def onReceive(message) puts "Hello " + message.who; endend

system = ActorSystem.create("GreetingSystem");props = Props.new(GreetingActor)greeter = system.actorOf(props, "greeter");greeter.tell(Greeting.new("Rocky Jaiswal"));

system.shutdownsystem.await_terminationThis is dead simple code, we create an Actor (GreetingActor) by extending UnTypedActor class, provided it an onReceive method which will receive messages, we created an Actor system, setup an Actor and passed it a message and voila we have a “Hello World” Akka program.

Now if you want to do this in a more “Ruby” way, there is an excellent lightweight Ruby wrapper around Akka called Mikka which will make your life a lot easier. Since I wanted to learn the API more, I did it in the more “close to the metal” way (sorry bad joke).

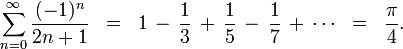

Now for something more interesting and complicated. For this we will again look at the Akka site here and calculate “Pi” with JRuby and Akka. Sounds exciting doesn’t it.

The formula we will use is -

This is splittable so that we can create multiple chunks like (1, -1/3, 1/5) and (-1/7, 1/9, -1/11) and so on where each chunk has a number of elements (three in the example above). As these chunks are individually calculated we just sum up their results.

To work up the CPU and to get better results our number of chunks can be as high as ten thousand and each chunk can have ten thousand elements. You can go even higher if you want.

Now we need to setup an Actor system where each worker applies the function to the elements of its chunk and reports back with the results. Depending on your CPU we can create “n” number of workers. We can then assign the chunks to the workers one by one.

Finally when the Master has finished calculating the sum of the results reported by the workers it can notify another Actor that the value of Pi has been calculated.

So we have three Actors now, the Master or the supervisor Actor, the Worker Actor and finally a Listener Actor which is notified of the final result.

The Master Actor can recieve two types of messages, a “calculate” message which is an indication to commence the calculations and a “result” message which is a wrapper around the result calculated by a worker.

Now let us see the program pi.rb :

require 'java'require 'scala-library.jar'require 'config-0.3.1.jar'require 'akka-actor-2.0.3.jar'

java_import 'java.io.Serializable'java_import 'akka.actor.UntypedActor'java_import 'akka.actor.ActorRef'java_import 'akka.actor.ActorSystem'java_import 'akka.actor.UntypedActorFactory'java_import 'akka.routing.RoundRobinRouter'java_import 'akka.actor.Props'java_import 'java.lang.System'java_import 'akka.util.Duration'java_import 'java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit'

#Wrapper for a calculate messageclass Calculateend

#Wrapper for a work unitclass Work attr_reader :start, :no_of_elements

def initialize(start, no_of_elements) @start = start @no_of_elements = no_of_elements endend

#Wrapper for resultclass Result attr_reader :value

def initialize(value) @value = value endend

#Wrapper for final resultclass PiApproximation attr_reader :pi, :duration

def initialize(pi, duration) @pi = pi @duration = duration endend

#The Workerclass Worker < UntypedActor class << self alias_method :apply, :new alias_method :create, :new end

def calculate_for_pi(start, no_of_elements) acc = 0.0 start_elem = start * no_of_elements end_elem = (start + 1) * no_of_elements - 1

(start_elem..end_elem).each do |elem| acc = acc + (4.0 * (1 - (elem % 2) * 2) / (2 * elem + 1)) end

return acc end

def onReceive(work) result = calculate_for_pi(work.start, work.no_of_elements) getSender().tell(Result.new(result), get_self) endend

#Masterclass Master < UntypedActor attr_accessor :start, :no_of_workers, :no_of_chunks, :no_of_elements, :listener, :pi, :no_of_results

class << self alias_method :apply, :new alias_method :create, :new end

def init_worker props = Props.new(Worker).withRouter(RoundRobinRouter.new(no_of_workers)) @worker_router = self.get_context.actorOf(props, "workerRouter") end

def onReceive(message) if (message.is_a?(Calculate)) (0...@no_of_chunks).each do |number| @worker_router.tell(Work.new(number, @no_of_elements), get_self) end else result = message @pi = @pi + result.value @no_of_results = @no_of_results + 1

if (@no_of_results == @no_of_chunks) duration = Duration.create(System.currentTimeMillis - @start, TimeUnit::MILLISECONDS) @listener.tell(PiApproximation.new(@pi, duration), get_self) get_context.stop(get_self) end end endend

class Listener < UntypedActor class << self alias_method :apply, :new alias_method :create, :new end

def onReceive(message) puts "Value of Pi - " + message.pi.to_s puts "Duration of calculation - " + message.duration.to_s

get_context.system.shutdown #get_context.system.await_termination endend

class MasterFactory include UntypedActorFactory

def initialize(listener) @@listener = listener end

def create self.class.create end

def self.create master = Master.new master.no_of_workers = 8 master.no_of_chunks = 10000 master.no_of_elements = 10000 master.listener = @@listener master.start = System.currentTimeMillis master.pi = 0 master.no_of_results = 0 master.init_worker return master endend

system = ActorSystem.create("PiSystem")listener = system.actorOf(Props.new(Listener), "listener")

props_2 = Props.new(MasterFactory.new(listener))master = system.actorOf(props_2, "master")master.tell(Calculate.new)If you read my explanation above this code is simple to understand, there is a minor hack or two to make Akka work on JRuby but most of this is self explanatory.

We can run this and see the output -

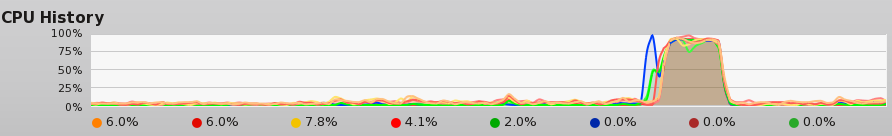

$ jruby pi.rbValue of Pi - 3.1415926435897883Duration of calculation - 5039 millisecondsFinally lets see the effect this has on my i7 CPU

As you can see all 8 virtual cores on the i7 CPU have been used with utilization close to 100% at the time the program ran. I think my experiment is successful, sorry for the longish post, I hope you had as much fun reading it as I had making it. Code shown above is available here.